Focus On: The future of the Czech Republic’s public media

10th June 2022

Big changes are coming to public media in the Czech Republic. From significant cost-cutting measures to planned amendments of the public media act, we summarise what lies ahead for Czech Television and Czech Radio.

By Desilon Daniels

Planned cuts to Czech Television

The Czech Republic’s public broadcaster, Česká televise (Czech Television), has announced plans to significantly cut both its budget and staff numbers. The media organisation will look to shave off nearly 1 billion crowns, while up to 250 jobs could be lost.

In a press release last month, Czech TV said its new public service sustainability strategy for 2023 and 2024 will feature a series of measures that will affect its television operation, programming, and original productions or investments. In total, the broadcaster will look to cut 910 million crowns (£31.6 million or USD 39.7 million) by 2024.

The measures are in response to a long-term trend that has seen a 36% decline in the real value of the television fee since it was last adjusted in 2008. The trend has been worsened by the recent significant acceleration of inflation and other financial pressures. The broadcaster said that a recent independent analysis of its costs showed that internal savings could no longer compensate for ever-increasing prices.

“In the last decade, Czech Television has managed to significantly expand the services provided to viewers, despite the declining real value of the television fee,” Petr Dvořák, Czech Television’s CEO, said. “For ten years, we have also pointed out that such a trend is not sustainable in the long term and that there will come a time when it will no longer be possible to maintain the current scope of public service without an increase in funding.”

The planned measures include “demanding changes and cuts”. While the changes and cuts would not be easy for the broadcaster, Mr. Dvořák said. “It is essential for us to maintain the status of Czech Television as a provider of relevant public services for all groups of viewers and as an institution that contributes to cultural development and the promotion of education.”

Key elements of the cuts include:

- A reduction in the number of jobs alongside a slowdown in the production of original programmes across all genres and related production capacities. The first wave of redundancies on Czech Television will occur in the second half of 2022 and will affect up to 50 jobs while another wave will follow in 2023 and 2024 and will affect up to 200 more jobs.

- A reduction in Czech Television’s investment programme, with a limit on investments in technologies to only those that are extremely urgent. Czech Television will also reconsider its current business strategy and increase the share of commercial advertising to the legally allowed limit.

- Restrictions on the production of sports programmes and limits on the ownership of broadcasting rights.

- A limit on the number of Czech TV channels. Notably, from January 2023, the broadcaster will cancel the ČT3 channel, the youngest Czech Television channel. The ČT3 channel was launched as a pilot in March 2020 in response to the coronavirus pandemic. However, its continuation is no longer feasible until the broadcaster’s sustainable financing is resolved. Further changes in the composition or number of CT channels could occur after 2024.

Read on the planned cuts in full: Czech Television plans cuts of 910 million crowns by 2024 (Czech)

Stalled attempts to safeguard PSM’s editorial independence

Under the previous government, Czech Television saw sustained pressure and attacks on its editorial independence. This included politically-motivated attempts to unseat its director general and the installation of government-friendly members to the Czech Television Council, the broadcaster’s supervisory body.

“It is essential for us to maintain the status of Czech Television as a provider of relevant public services for all groups of viewers and as an institution that contributes to cultural development and the promotion of education.” – Petr Dvořák, CEO of Czech Television

But under the new Petr Fiala government, amendments were drafted for the Act on Czech Television and Czech Radio, with the aim of creating additional institutional safeguards. Currently, a government can use its parliamentary majority to decide the composition of the boards, allowing it to place political allies within management structures. These amendments seek to undo this, and instead secure the independence of the governance boards for the future. Some of the proposals include:

- The establishment of clear criteria – for the first time – of who can be appointed to public media’s governing councils.

- The tightening of rules for who can nominate candidates.

- A change in the law to extend the powers to appoint the broadcasters’ government bodies from just the Chamber of Deputies to both chambers of parliament, thereby reducing the possibility of politicisation and improving the plurality of councils.

- Providing judicial oversight over dismissals of councillors.

Another key element of the amendments is the provision for sustainable funding for the public broadcaster, with automatic increases in the licence fee in line with inflation.

These amendments were developed with the input of journalists’ groups and media associations such as the NFNZ, CZ IPI and Rekonstrukce státu. A statement coordinated by the Media Freedom Rapid Response (MFRR) also signalled support for the passage of the reforms.

Read more: Czech Republic: Independence of public broadcasters must be insulated against future attacks

But while initial progress in the bill’s development was swift, the process has since stalled. This is partially due to the complicated legal challenges of passing such a reform, as well as competing priorities such as the war in Ukraine, high inflation, and day-to-day political reality.

🇨🇿 PMA joins @MediaFreedomEU partners in calling on the #CzechRepublic government to implement meaningful changes that will safeguard the editorial #independence of #publicbroadcasters @CRozhlas and @CzechTV

Joint statement⬇️#PublicMedia #PSM #PSBhttps://t.co/pX5NjoCtiB

— Public Media Alliance (@PublicMediaPMA) May 11, 2022

For instance, government legislative advisors rejected a version proposed by the Ministry of Culture due to uncertainties over its compliance with the constitution, IPI reported. The rejection stemmed from questions on whether it was acceptable to remove all members of the two public broadcaster’s supervisory bodies and elect fresh councillors. “The councils are currently occupied mostly by people appointed by the previous majority in the Chamber of Deputies (ANO-SPD-KSČM), some of whom took openly critical or outright hostile stands towards public media in the past,” the IPI report said. It is unclear when a new version of the amendment bill will be available.

Meanwhile, the latest round of appointments to the broadcasters’ oversight bodies has also slowed progress along with arrangements for the long-term financing of public media.

Wider landscape

The trajectory of media freedom in the Czech Republic was expected to change following the installation of a new prime minister and government in November 2021. But media advocates maintain that the situation has remained largely unchanged, with hopes for widespread media reform still unrealised.

Notably, it is believed that the recently released 2022 World Press Freedom Index does not accurately reflect Czech Republic’s reality. the Czech Republic rose 20 spots between 2021 and 2022 – where last year the country stood at 40/180, the 2022 index saw it rise to 20/180. But the higher ranking has brought on mixed reactions in the Czech Republic, IPI reported. Some attributed the rise as a result of a change in the index’s methodology and the decline of other countries’ rankings rather than improvements in the Czech Republic’s own media freedom.

“From the recent ranking this year, a casual reader may get the impression that the Czech Republic belongs to the world’s top in the field of free media. A year ago, however, it was [at] 40th in the same ranking. The ills of the Czech media landscape remained the same, only the name of the prime minister changed,” HlídacíPes.org reported.

Today, most big private media remain in the hands of oligarchs; a hostile attitude from the populist President Miloš Zeman and his supporters persists; and public media remain vulnerable to political pressures, an IPI analysis showed.

“The Czech media reality has not seen significant changes despite the hopes that came with last year’s election result,” IPI said. “The same people continue sitting in the media councils, the same president still has less than a year in office at the Prague Castle, and media owners remain the same. Going forward, both the councils and the president will change, but for the moment, concrete examples of positive change in the area of Czech press freedom are few.”

“We are engaged in a range of activities to support the free press because I think we can see quite clearly from the situation in Russia and Belarus that journalists are often the first victims of persecution in authoritarian regimes” – Czech Foreign Minister, Jan Lipavský

The analysis followed another IPI report published in March 2022 on media freedom and independence in the Czech Republic. It highlighted media capture in the form of the acquisition of many of the country’s largest private media outlets by a handful of oligarchs, who in turn used the media to promote their wider business interests. Further, it detailed how Babiš-owned media deliberately benefitted from government advertising funds. IPI recommended policy reforms to end the use of government funds to reward positive news coverage.

However, there were positives noted: the report also examined how a community of small digital outlets used high-quality investigative journalism to hold power to account despite their reduced resources.

The Czech Republic has identified media freedom as one of its priority areas as it prepares to take over the Presidency of the European Union in July.

“Our long-term activities in the UN council have focused strongly on media freedom,” Foreign Minister Jan Lipavský said. “We are engaged in a range of activities to support the free press because I think we can see quite clearly from the situation in Russia and Belarus that journalists are often the first victims of persecution in authoritarian regimes.”

There is still the opportunity for the current government to make significant positive changes to the media ecosystem in the Czech Republic. It needs to marry its strong words on media freedom with actual concrete actions, namely securing the independence and funding of the country’s public broadcasters. As it assumes the EU Presidency, it is a fitting time to make such bold moves as an example to other countries in the region.

Ceska televize public television broadcaster company logo on the headquarters building on March 9, 2018 in Prague, Czech Republic. Credit: josefkubes/iStock

Related Posts

10th May 2022

Czech Republic: Independence of public broadcasters must be insulated against future attacks

Joint statement calling on the Czech…

22nd March 2022

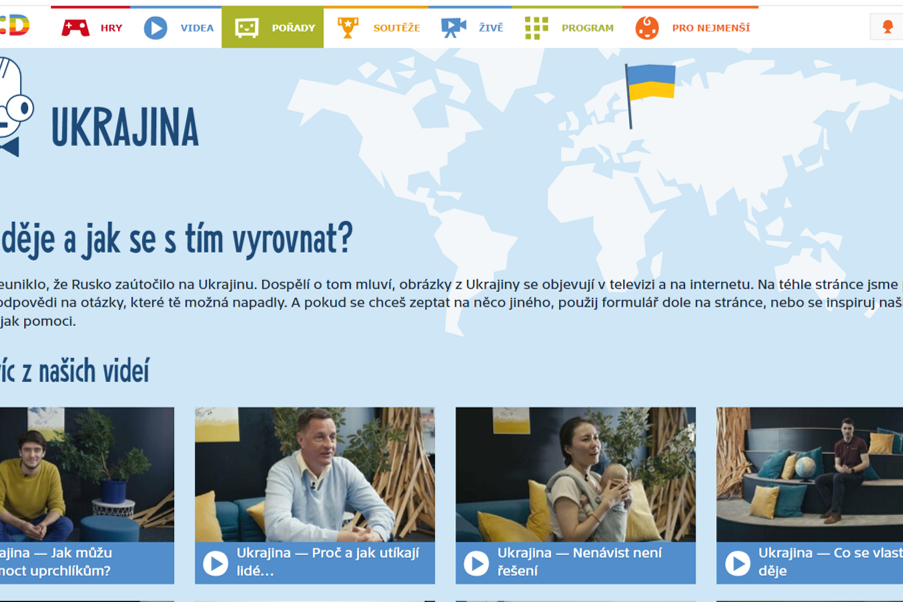

Czech Television’s services for children on Russia-Ukraine war

Czech Television has launched a new…