INSIGHT

Why we need a more humanitarian journalism

27th January 2023

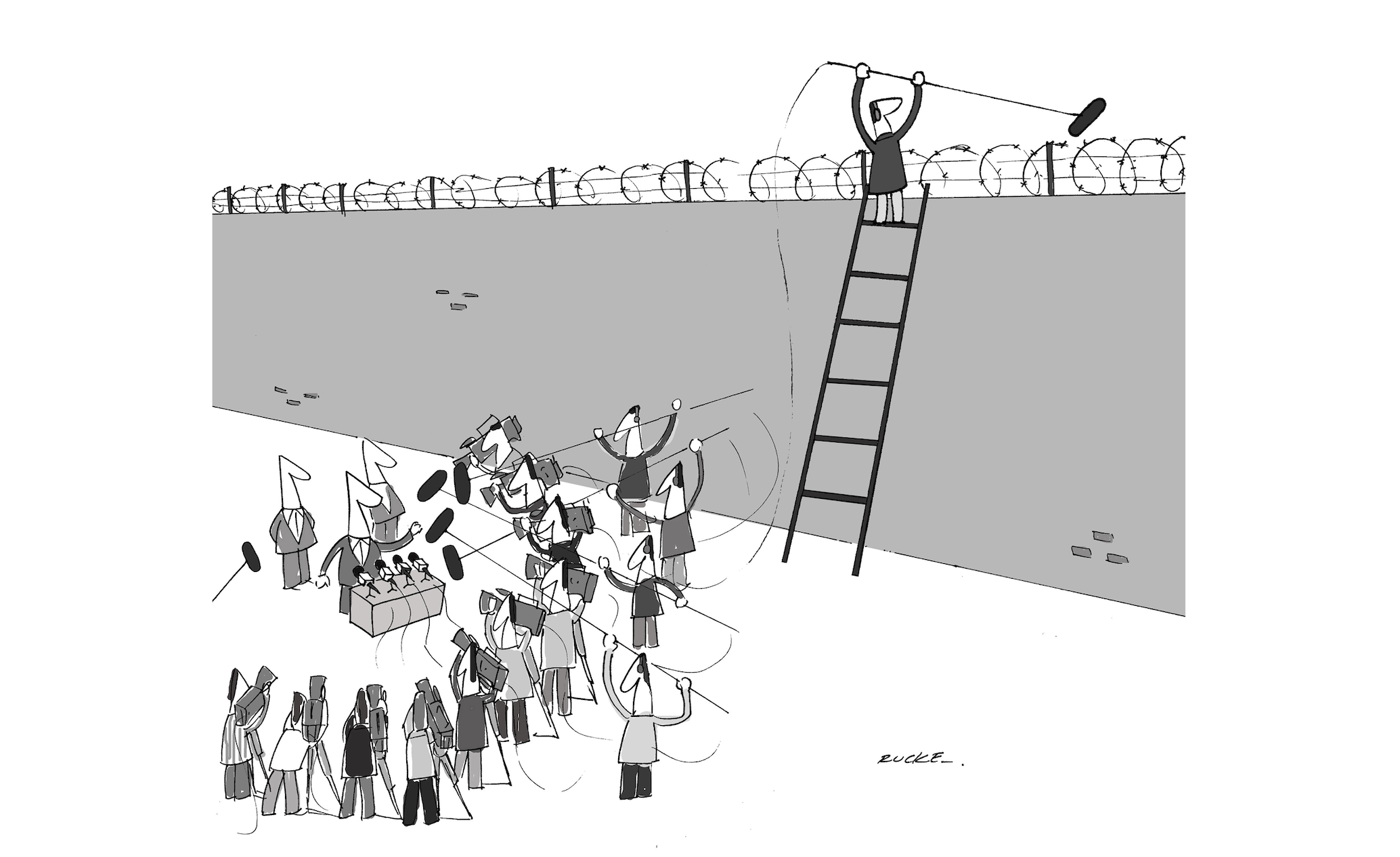

Some humanitarian crises receive more news coverage than others. But with the scale of news coverage linked to the level of international fundraising and support, a new book argues that we need a more humanitarian journalism, which cares less about how ‘newsworthy’ a crisis is and more about the scale of suffering.

By Dr Martin Scott, Prof. Mel Bunce, and Dr Kate Wright

Before the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the armed conflict in the eastern Donetsk and Luhansk regions was the second most under-reported humanitarian crisis in the world. In 2021, it was the subject of just 801 online news articles globally out of over 1.8 million articles analysed by Care International. In 2020, it received even less media attention – just 702 articles. During this time, around 3.4 million people in eastern Ukraine needed humanitarian assistance.

Other consistently ‘forgotten’ crises include the 1.2 million people in Zambia experiencing acute levels of food insecurity, which received just 512 online news reports in 2021; and the 2.8 million people in need of humanitarian aid in Honduras because of chronic poverty and violence, which received just 3,920 online news articles in 2021. To put these figures in context, during the same period, there were 91,979 online articles globally about the announcement that actors Ben Affleck and Jennifer Lopez were dating again, and 239,422 news articles about billionaires Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk taking space flights.

However, not all humanitarian crises are ‘forgotten’. For example, in 2021, the humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan was the subject of nearly half a million (475,744) online news items – more than 33 other crises combined. Similarly, in 2022, the war in Ukraine drew a vast amount of international media attention. At its peak, it was the subject of 35 percent of all online global news coverage.

Explore: Latest PSM research and resources

Such extreme disparities in media attention are a longstanding and well-documented feature of international news coverage and the result of conventional journalistic norms and practices, as well as structural influences. Research has repeatedly demonstrated that the volume of international news coverage a humanitarian crisis receives is primarily a reflection of its geo-political significance and its resonance with journalistic news values – rather than the number of people affected. Dr William Adams, for example, found that, ‘the severity of foreign natural disasters explains less than ten percent of the variation in the amount of attention they are given in nightly U.S. television newscasts’. Instead, as Professor Suzanne Franks put it, ‘Western self-interest is the precondition for significant coverage of a humanitarian crisis’.

These disparities in media attention – and this disconnect with levels of suffering – have important consequences. They can compound the limited international political attention that most crises receive, because politicians are under less pressure to act. The under-reporting of humanitarian crises can also exacerbate disparities in the amount of funding they receive from international donors. For example, our own research recently demonstrated that a large amount of sudden-onset, national news coverage can pressure governments to allocate greater support to a humanitarian crisis – even if the level of unmet need does not require it.

Listen toour podcast

Uncovering and exploring the biggest

issues facing public media

But the episodic and selective nature of conventional news coverage of humanitarian crises is not inevitable. Our recent book – based on a 5-year study, involving over 150 in-depth interviews – documents the unique reporting practices of a small but influential group of humanitarian journalists who defy conventional approaches to covering humanitarian crises. Instead, their work is shaped by both journalistic and humanitarian principles. For example, their strong adherence to the humanitarian norm of ‘moral equivalence’ – the idea that all lives have equal worth – means that they continue to cover humanitarian crises even when these do not correspond with conventional news values.

For instance, in 2021, when eastern Ukraine was almost entirely overlooked by most news outlets, The New Humanitarian continued to publish in-depth stories about the impact of the Covid pandemic on the conflict, for example, and the inadequacies of mental health support for children affected by the war. Similarly, after the Russian invasion in 2022, when global media attention focussed heavily on Ukraine, humanitarian journalists continued covering other ‘forgotten’ crises in Malawi, Guatemala, Burundi, Niger, Zimbabwe and elsewhere, which conventional news outlets were largely ignoring.

But reporting under-reported crises is not the only way humanitarian journalists’ professional practices differ from conventional journalism. Their adherence to the humanitarian principle of ‘moral equivalence’ leads them to amplify marginalised voices connected to humanitarian crises, such as affected citizens and local volunteers. For example, The New Humanitarian’s article about children’s mental health in eastern Ukraine in 2021, focussed primarily on the testimonies of children themselves, along with their guardians, parents, and grandparents.

In addition to ‘reporting under-reported crises’ and ‘amplifying marginalised voices’, humanitarian journalists seek to ‘add value’ to mainstream news coverage of humanitarian crises – in accordance with the humanitarian principle of ‘making the most difference’. This is usually achieved by providing longer-form, explanatory journalism and/or by experimenting with different formats. For example, in its coverage of humanitarian issues in Africa, HumAngle regularly makes use of infographics, cartoon illustrations, Twitter Space discussions, geospatial tools, explainer videos, documentaries, interactive dashboards, and weekly podcasts.

In 2023, 339 million people in 69 countries will need humanitarian assistance, according to the UN. This is an increase of 65 million people compared to the same time last year. In a world of increasingly severe humanitarian crises, it is important to ask – are traditional news values serving audiences well enough? Humanitarian journalists show us that another kind of crisis reporting is possible.

This article is based on an extract from Humanitarian Journalists: Covering Crises from a Boundary Zone by Dr Martin Scott, Dr Kate Wright, and Prof. Mel Bunce

The header image was originally featured in The New Humanitarian | Why so many humanitarian crises are ‘forgotten’, and 5 ideas to change that

About the authors

Dr. Martin Scott is an Associate Professor in Media and Global Development at the University of East Anglia.

Prof. Mel Bunce is a Professor of International Journalism and Head of the Journalism Department at City, University of London.

Dr. Kate Wright is a senior lecturer in Media and Communications, Politics, and International Relations at the University of Edinburgh.

Related Posts

28th September 2022

Journalism Makes a Difference – World News Day 2022

This World News Day, PMA is proud to…

2nd December 2021

The importance of ethics when reporting on conflict

"A regional outline of the issues and…