ANALYSIS

Independent and free media saves lives

10th March 2023

In the aftermath of major crises, the presence of independent public interest media is vital to ensure effective and critical coverage of recovery efforts.

Natural disasters are inevitable, unpredictable, and in a warming climate, ever more frequent. That these events happen is no one’s – or no government’s fault.

But that does not mean that when these disasters happen, no one is unaccountable for their impact. As seen in Turkey following last month’s devastating earthquake, developers have been accused of not building to the regulations, with over 100 contractors facing arrest. Meanwhile the authorities have been criticised for not enforcing these regulations. Over 50,000 people are estimated to have died, with the cost of the damage billed at US$34 trillion.

In the hours and days that follow natural disasters, coverage of these events are extensive and global. Journalists examine the immediate damage, the impact on peoples’ lives, and the instant political wrangling. They analyse statistics concerning deaths, displacements, and damage.

But once the international media leave, scrutiny must remain. As authorities survey the damage and make changes over the following weeks, months and years, a free and independent media is crucial to keep watch, keep the public informed, and hold power to account.

“No famine has ever taken place in the history of the world in a functioning democracy,” wrote Amartya Sen. Free media, reporting impartially on government action, underpins functioning democracy. Sen lived through the Bengal famine of 1943 and witnessed the suppression of the Indian domestic press and the blind eye of the UK press.

Without a free media, how does the public know what has happened? How do they make demands and clamour for change? How can politicians understand public sentiment if a free media is not there to give those opinions a platform?

“It’s a delicate balancing act but dissemination of emergency information and providing a rigorous independent scrutiny of Government are essential and complementary. One should not preclude or interfere with the other.” John Barr, Head of Communications, RNZ

Sen argues a free media ultimately improves outcomes for the nation. Governments make policy to avoid becoming the object of blame. Democratically elected governments “have to win elections and face public criticism, and have strong incentive to undertake measures to avert famines and other catastrophes.”

How does this differ in countries without a free media? Reporting in Turkey regarding public criticism of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has predominantly come from international outlets. Independent journalists have instead been detained, imprisoned and harassed. Twitter was temporarily shut down.

But once international news outlets leave, who maintains the scrutiny to ensure subsequent earthquakes will not be so catastrophic? Independent public interest news outlets in Turkey try, but pressure on them from the government remains severe.

Listen toour podcast

Uncovering and exploring the biggest

issues facing public media

New Zealand – a country with one of the freest media environments – offers an interesting example. It too is prone to natural disasters. In early February, a week after the earthquake in Turkey and Syria, New Zealand was struck by Storm Gabriel, described by the Prime Minister as “the most significant weather event” this century. The disaster claimed the lives of 11, displaced 2,500 people, and repairs could cost 8 billion NZD.

“Many communities have been isolated and there has been significant disruption to critical transport routes and infrastructure,” John Barr, Radio New Zealand’s (RNZ) Head of Communications, told PMA. “The social and economic impact will be felt for many years.”

When natural disasters happen – as they often do in New Zealand – RNZ is an important part of the overall management response. During Storm Gabriel, journalists reported from all affected areas and programming on the main radio station was rescheduled so listeners could access round the clock coverage.

“RNZ is a designated Lifeline Utility under the New Zealand Emergency Management Act,” Mr. Barr said. “This means the public broadcaster has obligations to maintain core services in the event of a natural disaster or other civil defence emergency. In a natural disaster public access to lifesaving information is often limited if mobile technology, or online and digital channels of communication are unavailable when power sources are cut. Battery powered, solar or wind-up radio is often the only source of vital information for isolated communities.”

RNZ is not alone in having this special designation. In recent years, there has not been a shortage of emergencies in which public broadcasters have demonstrated their role, from the wildfires in Australia, to flooding across Europe.

It is common around the world for public broadcasters to occupy this role, given their near-universal reach and ability to distribute public service information.

But there is an inherent tension here, between the organisation as an independent public broadcaster and the organisation as a lifeline utility. “There is always a tension in communicating information from government agencies without having complete editorial oversight and RNZ will only carry such information after very careful consideration – or if a formal legal declaration of a state of civil defence emergency has been made – indicating immediate or potential threat to life,” Mr. Barr said.

What distinguishes a public service broadcaster, however, is the scrutiny that it applies, and the questions that it asks: How did this happen? Could the extent of the impact have been mitigated in any way? Is there any culpability?

“RNZ actively scrutinises the actions of regional and national authorities before, during and after events and the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) accepts that RNZ has a dual role in holding power to account. … It’s a delicate balancing act but dissemination of emergency information and providing a rigorous independent scrutiny of Government are essential and complementary. One should not preclude or interfere with the other.”

RNZ’s role is codified into a Memorandum of Understanding, which is critical to ensure its independence and integrity is maintained throughout the event. In the weeks and months which follow, RNZ’s role becomes about holding power to account and scrutinising the policy and legislative reactions that may follow on.

It is imperative that public service media maintains this commitment. Audiences turn to independent public broadcasters in times of crisis, knowing they are accurate and trustworthy sources of information. And with natural disasters ever more frequent, these public broadcasters serve as not just a life-saving utility carrying public service messaging, but also as a check and balance on the strategies adopted to mitigate and adapt. This role is an essential democratic public service, and lives depend on it.

Related Posts

27th July 2022

“A vital tool”: Why RNZ turned to shortwave after the Tongan volcanic eruption

When the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai…

25th February 2022

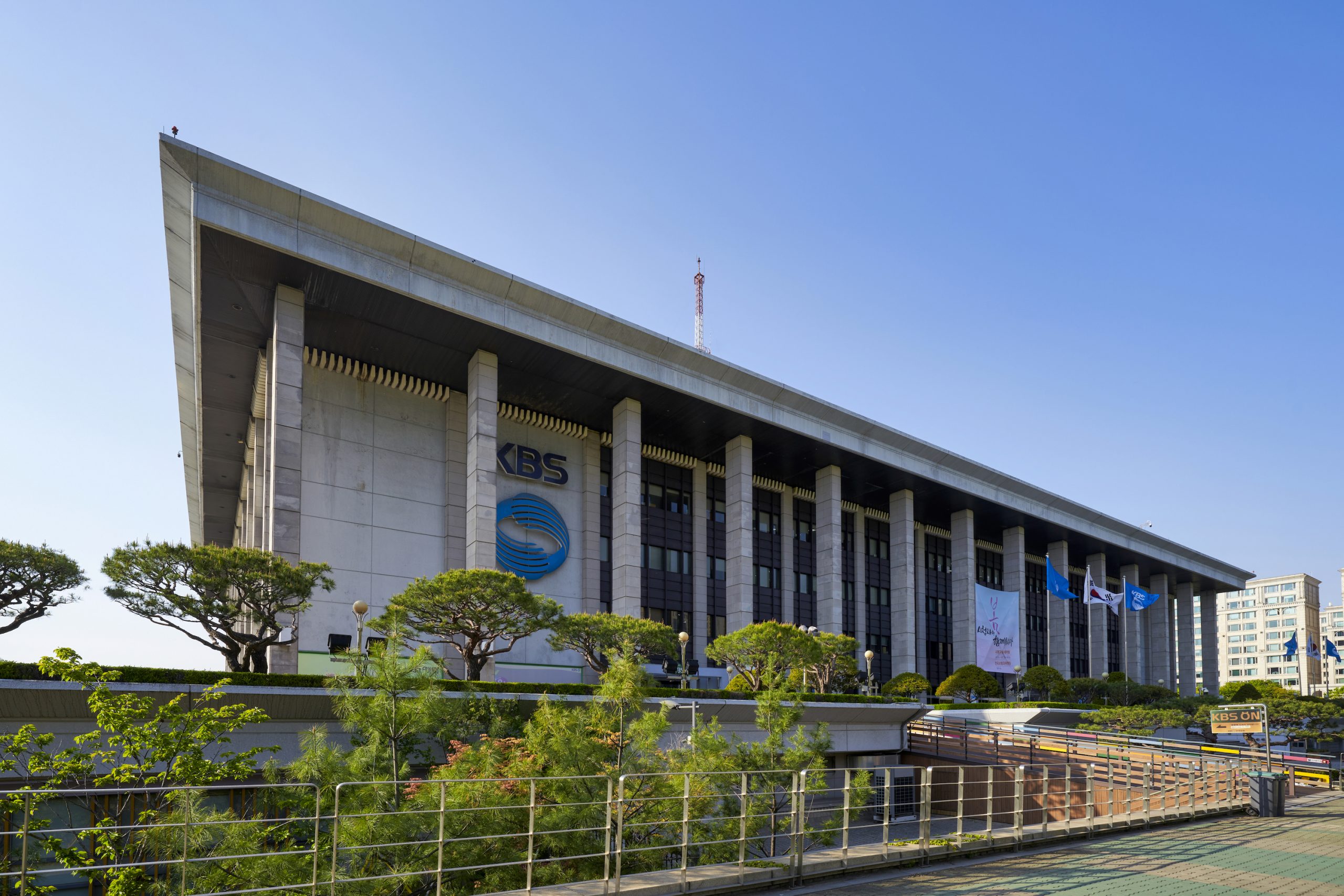

KBS’ Covid-19 emergency broadcasting helps country’s pandemic response

The Korean Broadcasting System’s (KBS)…