INSIGHT

CBU 2023: PSM in the 21st Century

22nd August 2023

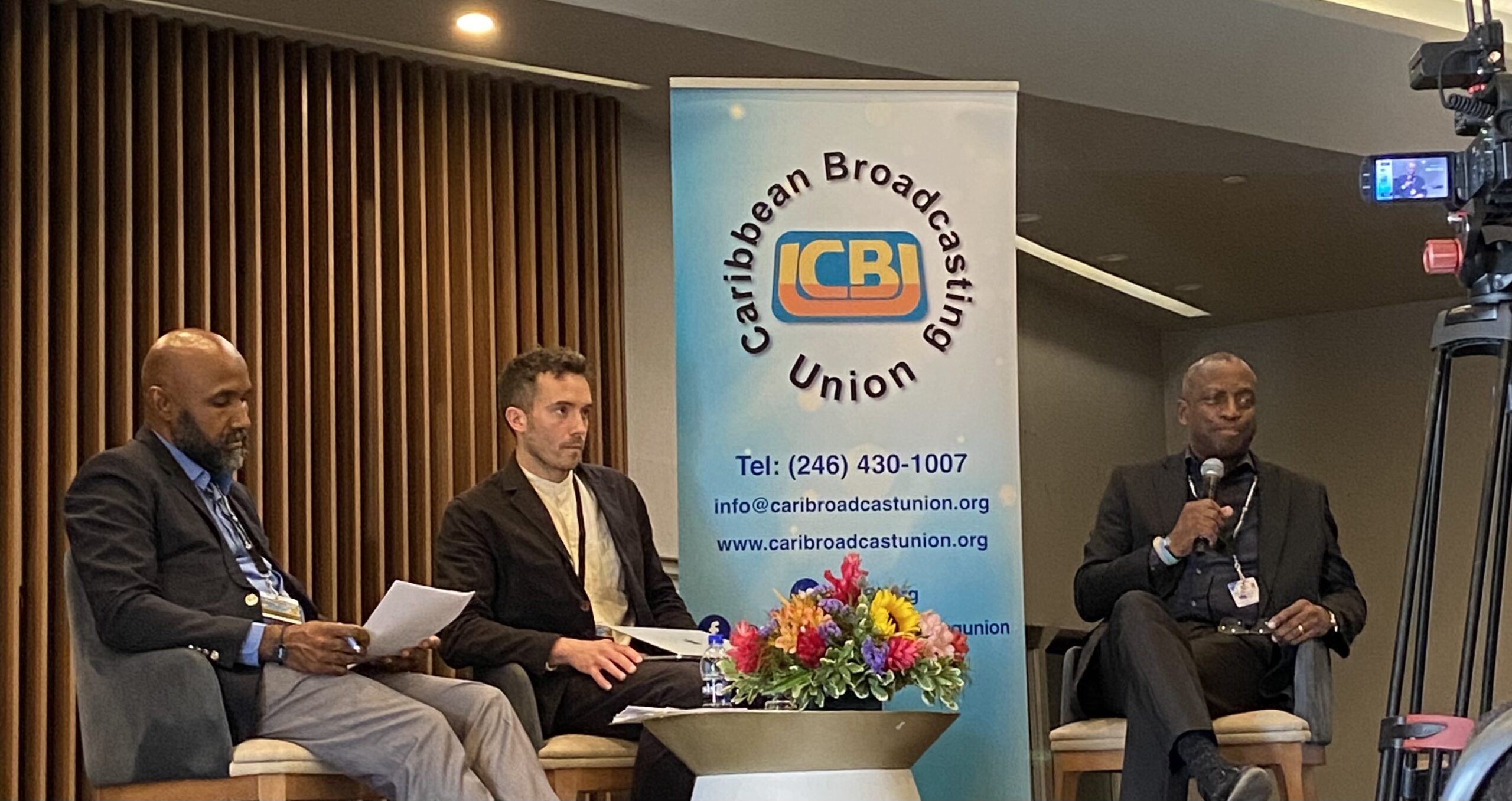

In a speech at the Caribbean Broadcasting Union’s 54th Annual General Assembly, held in Antigua on 14 – 16 August, the CEO of the Public Media Alliance, Kristian Porter discussed some of the challenges and opportunities for public service media (PSM) in the 21st Century.

This speech has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Friends, colleagues, delegates. It is a huge privilege to be with you again for this year’s CBU AGA.

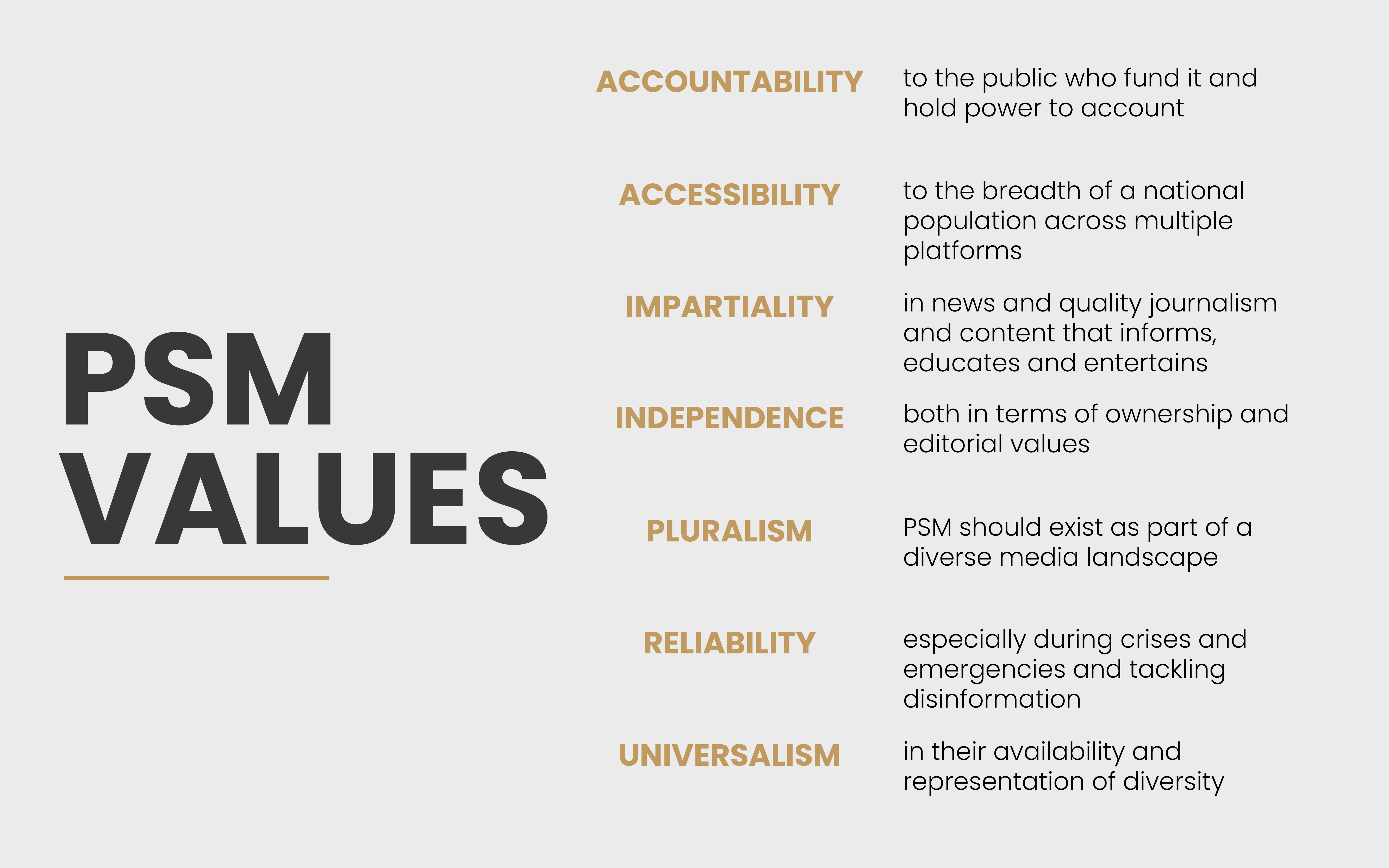

It’s very easy to preach to the choir about the values of public service and public interest media. The benefits to society and democracy of having access to public media which is well-resourced, independent, accountable, and impartial – that which entertains, informs and educates – are clear. In an era defined by disinformation, misinformation, hate speech and propaganda, the presence of a trustworthy media organisation with such values is critical. It makes sense. Case closed. Argument won. I should sit down.

But there’s a reason why organisations like the Public Media Alliance and the CBU continue to exist. The realities of ensuring the viability of public service media have never been for the faint hearted, even more so now as some enter their centenary. And let’s make no mistake – these organisations, in upholding these values, are underpinning democracy. They hold power to account, they produce a more informed and participatory citizenry, and they enhance understanding and cohesion between communities.

But there is also something else that unites these most vital of democratic institutions… and that’s the contemporary challenges that they face. Public service media, in all their forms, globally, face a number of common crises… some minor, some drastic, and some, frankly, existential.

We’re 23 years into the 21st century and it’s clear that there is an abundance of opportunities for public service media to reach audiences, to cover news in new and innovative ways, to hold power to account, whether that’s through the availability of data, AI tools, or the sheer ability to communicate through multiple services. But these opportunities all come at a cost, and can be limited in their use due to a number of common challenges.

Funding

Sourcing sustainable levels of public funding is more precarious than ever. The impact of COVID, war and other crises, climate change… have all caused the cost-of-living to spiral, and convincing both the public and politicians that public service media is a worthy and necessary expense is increasingly difficult. And the threat is two-fold – media businesses are increasingly expensive to run, especially when competition for commercial revenue and audiences is growing and moving away from traditional platforms.

As such, licence fee evasion rates are increasing. They’re considered high in the UK at around 9%, the Republic of Ireland at 15% … but in South Africa it’s at 80%, resulting in drastic cuts and redundancies at a time when the South African public broadcaster and the country are adapting to digital transition. In France, the licence fee has been dropped altogether with no real long-term alternative. In Switzerland, there is likely to be a referendum in the next year or two whether to drastically cut the licence fee. And in South Korea, changes are being forced upon the licence fee mechanism by the government, which could result in an existential decline in funding. This is also, in part, an issue of control.

Scandinavian countries meanwhile have transitioned to tax-based funding models while in Germany they use a progressive household fee. But these transitions require strong legislative and regulatory support for independence and crucially, backing from the public. And this bit is significant. No matter the funding mechanism, the public need to be convinced of your value as public service and public interest media. They need to understand why the work public media does is so important, and why they should support it.

Concerningly, trust in public media is declining. And as public media continue their efforts to justify their worth and their value to their stakeholders – the public – they are now facing more competition for a share of the public’s money, the public’s attention and in turn, advertising revenue. It’s a fight for eyeballs, and we need to consider who ALL public media are up against:…. not just their traditional rivals in private media, but now big tech. This is particularly the case here in the Caribbean.

And this fight has a very real impact on the purse strings of public broadcasters. Two companies in particular, Google and Meta, now soak up 80% of advertising revenue in Canada alone. This money is being siphoned away from both local private and public media into the hands of multinational behemoths, putting added pressure on news outlets, at a time when new equipment is needed to fully transform and keep pace digitally.

Media freedom and the operating environment

The availability of funding is also influenced by the operating environment that public media find themselves in. Public service and public interest media must be seen to hold power to account on behalf of the public. So, for detractors of public media, influencing and controlling the source of funding is critical if you want to influence the narrative. Where media freedom and checks and balances are weaker, there are more opportunities for governments to assert pressure on funding and even capture media entirely.

“No matter the funding mechanism, the public need to be convinced of your value as public service and public interest media. They need to understand why the work public media does is so important… and why they should support it.”

Most recently we’ve seen attempts in Israel, where there have been threats of privatisation, removing advertising income and giving the government more influence over the media regulator. Even one of Europe’s largest public broadcasters, Rai in Italy, is not immune. The EU has raised its concerns about this issue.

Since last year’s elections, Israel has descended 11 places to 97/180 in the 2023 Reporters without Borders Press Freedom Index. And it’s not alone, since 2013, the number of countries considered as being in a “good” situation for media freedom has fallen from 26 to just 8, while those considered to be in the worst category has risen from 20 to 31.

Polarisation and weak protections for journalist safety on- and offline are significant factors, as is the prevalence of SLAPPS, where journalists are arbitrarily targeted with legal action for simply doing their work. Some public broadcasters, like CBC/Radio-Canada and Dutch public broadcaster NOS, have even resorted to removing their logos from equipment due to concerns for journalist safety.

And the Caribbean region isn’t exempt from this decline. While Jamaica and Trinidad & Tobago continue to lead the way, there has been an overall decline regionally, with the OECS countries in particular falling from 55th to 93rd this year.

Journalist safety – whether physical, psychological, or online – are all in decline, especially for minority groups, women journalists, and those from the LGBTQ+ community. According to a global survey of 714 women journalists by the ICFJ, 73% experienced some form of harassment online, while 25% received threats of physical violence, such as sexual harassment or death threats. Abuse spills over into the real world – physical violence – and campaigns of harassment only serve to inspire self-censorship, and in turn silence the very news outlets that inform democracy. It also affects staff retention and deters younger generations from entering the profession.

Subscribe toour newsletter

Keep updated with the latest public

media news from around the world

The pace of change

So, the challenges I’ve outlined so far have long been with us in various forms. But the need to transform digitally, to keep pace with fragmenting audiences and technology, to reach the under-30s, to maintain relevance and prominence is applying transformative pressure on public media. Some public media are adopting digital-first policies, but it means we are all using, and increasingly relying upon, rapidly evolving third-party platforms, whose ownership lies outside our jurisdictions.

I want to talk about an emerging problem here, and that’s limited bargaining power, over reliance, and limited control. Let’s start with TikTok. In 2022, the BBC announced TikTok as a priority platform to reach younger audiences despite its unpredictable algorithm for news content. The BBC hired TikTok-focussed journalists and it now has 1.9 million followers on its News account.

Earlier this year, a number of public broadcasters limited their use of TikTok, because of cybersecurity and privacy concerns, about the app’s access to users’ data, and where this data was stored. We know these concerns are valid: In April, for example, a Financial Times journalist reported that she was being tracked by TikTok staff in both China and the US, via an account that was in her cat’s name.

But still, we see that some public media lack platform-specific strategies and codes-of-conduct to account for the variations between platforms.This needs to change. Public media need to keep pace.

PODCAST: Should public service media leave social media?

In March and April, public media organisations in Denmark and Sweden started to advise staff to delete TikTok from corporate devices because of security worries. This isn’t simply a concern we should apply to TikTok… Third-party platforms – whether it’s Instagram, LinkedIn, or Facebook – are often opaque in their data handling, and we are right to question their practices.

And then there’s Twitter/ or X. You may have seen Twitter’s mislabelling of independent public media as “government-funded or state-affiliated”, which had the potential to sow distrust in some of the world’s most trusted media brands.

This labelling was done without consultation and was only reversed following widespread criticism. But the damage, for many, has been done – broadcasters like Swedish Radio, NPR and CBC/Radio-Canada consequently curtailed their output on the platform. And in Australia, ABC announced last week that it would essentially shutter its Twitter services both due to this and the proliferation of hate speech on the platform.

And then there’s Meta, which has essentially decided to “un-friend” the Canadian news industry in response to the country’s Online News Act. The Bill is modelled on a similar law in Australia, and is designed to address the gross imbalance of advertising income which I mentioned earlier, and redistribute it to the actual producers of news content.

“If audiences can’t see you, discover you, use you, why would they value you?”

But Meta – instead of paying the news providers – has instead decided to block news content for all Canadian users, in a move which will have significant repercussions for news providers and audiences across Canada. It will restrict users’ access to trusted sources of news and verified information on its platforms, and will also prolong the crisis faced by many outlets, whose revenue has suffered a dramatic downturn over the previous two decades.

The situation highlights the financial and competitive imbalance between the producers of news and the platforms they now rely on for visibility and distribution. While Canadian news organisations have united to call for investigations into Meta’s abuse of its dominant position, the question is whether they have the combined weight to challenge their decision, let alone the government. This is a concern for us all.

As trusted public service media mandated to provide accurate, verified, and trusted news and information, the potential to be blocked for simply receiving fair compensation is alarming. And as audiences fragment and increasingly use social media to access news, these issues compliment concerns about brand visibility and discoverability. After all, if they can’t see you, discover you, use you, why would they value you?

What needs to be done?

Now this is where it gets difficult. Positive attribution and loyalty to any public media brand is preferably gained through trust. Audiences need to know what you do, how you do it, why you’re the best… and why they should pay for and trust you.

This goes for politicians too: regardless of media model, they need to know what independent public interest media does for society and democracy. Ultimately, this is a media literacy issue and it cuts across all the challenges I’ve discussed here today.

“I firmly believe that for their common values to continue, for their content to stay relevant, for them to have impact, that collaboration between them has never been needed more.”

There is a need for public interest media to better explain and demonstrate what they do. So how are they doing this?

In Germany, PSM have launched online teaching materials covering factchecking, safety on social media, and how public media is funded and why. There is also a joint initiative among 60 media organisations called Schau Hin or “Look At” to provide parents with support in media education, especially regarding data protection and trends.

Next year, the Public Media Alliance will look to roll out a new initiative in four countries in this region with these projects in mind. But it can also be simpler than this, such as building media literacy into your existing formats and schedules. The BBC now offer explainers regarding their investigations via their news website and have also launched a campaign to complement its programming to highlight its editorial values. It’s also about demonstrating accountability. In Belgium, there is a specific “media news” section of RTBF’s news website, and Swedish Radio runs “morning seminars” for listeners on media issues.

And it’s also about transparency. If you use AI, for example, in your content or to personalise experiences, then explain why, where and what its limitations are. Reassure audiences about what you do and be accountable. Media literacy clearly cuts across into funding too. It enables greater support for what you do from your audiences. So convince them of your value.

But media freedom issues are more hard fought. They require constant advocacy… I’ll come to this later…. But there are steps that can be taken internally, by you, to keep journalists safe, especially online.

- Dare to be outspoken. For example, collaborate with others in support of journalist safety.

- Establish an open, supportive culture within your organisation and launch reporting mechanisms like a specific mailbox for staff to share incidents and have a point of contact for those facing abuse.

- Prevention is key. Limit the number of comments and responses to a story on social media, and remove pressure on staff to be on social media. Engage staff with regular social media “health checks” and take stock of the personal info they have online.

Journalist safety concerns are damaging for democracy – fewer people join the profession if it’s seen to be unsafe, which ultimately means fewer people holding power to account.

The challenges threatening public service media in 21st century are profound, but this doesn’t diminish their value. The struggle is how to combat these challenges when the forces behind them – whether political or market driven – are colossal. One of the simplest answers is, frankly, collaboration – that’s learning from one another, joint initiatives, committing to projects that ensure the viability of public media and maintain their relevance in the digital age. After all, where there are shared challenges, there are shared solutions, especially where values align.

So to conclude. One of the biggest questions we now face is: how do they remain relevant for audiences, be visible, and be viable? Many of the challenges I’ve listed today are far bigger than any one public media organisation. They are systemic, global and continuously and rapidly evolving.

Public media are inherently part of this wider competitive and commercial push for an audience. This often sees public media having to increasingly prioritise their commercial footprint. But I firmly believe that for their common values to continue, for their content to stay relevant, for them to have impact, that collaboration between them has never been needed more. There is hope. There has been growing recognition for the role of public media in the past year in places like Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, Taiwan and even Slovenia because, in part, they have visibly demonstrated their value and their values.

I certainly haven’t got all the answers, but I’d really welcome us finding the time here to discuss how we can all better collaborate and coordinate our responses to common, global challenges like the ones I’ve raised today. Thank you.

About the author

Kristian Porter is the CEO of the Public Media Alliance.

Related Posts

12th January 2023

Going all digital? BBC, France Télévisions consider online-only futures

The BBC is eyeing an online-only future…

1st November 2022

Switching from analogue to digital in the Caribbean

In the Caribbean, conversations around…