With 2019 being the UN Year of Indigenous Languages, how do public media organisations ensure the fair representation of indigenous cultures and languages?

For citizens to be informed as well as entertained, public service media (PSM) need to engage diverse audiences with credible, high-quality content.

A key pillar of PSM is to therefore be representative and accessible to all within a nation. Afterall, they must provide content for the breadth of the public that pay for them. But this is no mean feat, with nations rarely being culturally or linguistically homogeneous.

Of course, many PSM lead the way in providing services for a variety of major language groups. In Belgium, public media is split into three organisations representing the three dominant languages: French (RTBF), Dutch (VRT) and German (BRF). In Switzerland, SRG-SSR operates in four languages – German (SRF), French (RTS), Italian (RSI) and Romansh (RTR) – each represented by a regionally associated organisation, which is run through a central headquarters in Bern (SRG-SSR).

It is clear then that ensuring accessible, representative and well resourced content for all is complicated, where in some cases a public broadcaster is split to ensure fair coverage. But how do public broadcasters represent more minority or marginalised languages, especially those used by indigenous communities?

More broadly, some media organisations claim a lack of resources and prioritisation as the reason for limited representation. Yet a number of public media organisations are leading the way in innovating their attempts to not only represent, but also promote their country’s minority languages. Here we explore just a few examples, from Peru, New Zealand, Canada, Scandinavia, Australia and Italy.

Reviving indigenous languages

There are approximately 47 indigenous languages in Peru, with Quechua – 4 million fluent and approx. 10 million intermediate speakers in Peru alone – being the most widely spoken indigenous language in Latin America.

Quechua was recognised as a national language alongside Spanish in the 1970s but it lacked dedicated media spaces, with it taking considerable time for the language to be socially disentangled from discrimination and misrepresentation.

In 2016, Peruvian public broadcaster, TV Peru, tried to shift the situation by launching a unique news show in the Quechua language. The programme, ‘Ñuqanchik’ (Us) aims to widen indigenous groups’ representation, which is often commodified and subject to folkloristic portrayals.

“Quechua was synonymous with social rejection – and thus became synonymous with discrimination,” said Hugo Coya, director of Peru’s TV and radio institute. “Speakers often didn’t want to admit they spoke Quechua in order to be accepted by Spanish-speaking society.”

In addition, the programme also hopes to bridge divides between Quechua and Spanish speakers by giving a platform where stories from the perspective of the Quechua community can come to light.

“This, we believe, will transform the relationship between the government, the state, and those people who speak a language different from Spanish,” said Fernando Zavala, the country’s Prime Minister.

And similar initiatives are becoming a reality for other indigenous languages in Peru. In November, the National Institute of Radio and Television of Peru (IRTP) launched Ashi Añane (Our voice), a programme in Asháninka and Jiwasanaka (Us) in Aymara.

The programme’s journalists and producers are almost all native speakers and the use of local languages becomes extremely useful when it comes to conveying crucial information, such as the State’s health and disease prevention campaigns. This, for the Peruvian government, a way to give back to communities that have been wronged throughout the country’s history.

“The Asháninka were one of the peoples most hit by terrorism during the era of Sendero Luminoso,” Coya said to the Knight Center. “There are terrible, dramatic stories of this struggle that little or nothing is known about. In a way, this space is paying, in part, the debt that the State historically has with this people.”

Incorporating languages

For New Zealand’s public broadcaster, Radio New Zealand (RNZ), it is not simply a case of providing separate language content for indigenous audiences but also incorporating the Māori language, te reo Māori, into their predominantly English-language services.

As with many former colonies, New Zealand has a complicated history with its indigenous communities, and RNZ’s approach to incorporating te reo Māori into its content is part of its mandate to ensure its services are more accessible and available to all while representing the nation’s diversity.

This reflects RNZ’s latest Māori strategy, which emphasises the normalisation of the language across all of its services. These initiatives include ensuring te reo is heard in almost all news bulletins, providing linguistic training to on-air staff, improving representation by partnering with Māori-led media and gauging the public response to further improve te reo services. The strategy also includes internship opportunities for Māori graduates who want to improve their journalistic skills.

Yet despite mostly positive feedback, the recent drive to open and sign-off English-language content with te reo Māori has been met with some derision. Critics claim that te reo is being forced upon a majority-English speaking population, despite it being an official language of New Zealand. Others claim the language is already provided for by Māori Television, the country’s dedicated indigenous broadcaster – which also broadcasts in English.

This led to a response from RNZ CEO, Paul Thompson, who wrote that despite the pockets of criticism “we shouldn’t underestimate the signal the national broadcaster sends when it normalises and socialises the use of te reo”. He emphasised that regardless of RNZ’s mandate to provide te reo content, its growing use by staff will help to spark a national conversation that will change people’s thinking about one of Aotearoa’s (New Zealand’s) official languages and “reflect all that is unique and important to a nation of many parts but with a single destiny.”

You can listen to RNZ’s Maori Greetings and learn more about the RNZ initiative here.

“We shouldn’t underestimate the signal the national broadcaster sends when it normalises and socialises the use of te reo” – Paul Thompson, CEO Radio New Zealand

Collaboration

But cultural and linguistic boundaries do not observe national ones. In Scandinavia, many people share a common heritage to the indigenous Sámi people, whose traditional homeland stretches across northern Norway, Sweden, Finland and the Murmansk Oblast region of Russia.

But with an estimated 75,000 Sámi people living across the region, there is no one distinct language. Instead there are 10 spoken languages, six of which have their own written standards, with not all being mutually intelligible. Moreover, Sámi culture and languages are not bound by national borders, with some spoken in three, if not four, countries.

This, alongside a fragmented Sámi population, may make representation by a national public broadcaster seem like an uphill struggle. Yet, with a history of considerable discrimination against the Sámi people, the need for effective representation is absolutely essential.

The Finnish public broadcaster, Yle, has made significant steps toward offering plural content in three Sámi languages (Northern Sámi, Inari Sámi and Skolt Sámi). Launched in 1947, Yle Sápmi hosts a website and broadcasts eight hours of Sámi language radio content each day nationwide. But it wasn’t until 2013 that Yle also launched a Sámi television news service, broadcasting daily at 4:45pm for five minutes on its flagship channel, TV1.

Yet regardless of Yle’s mandate to serve all Finns, the resources needed to provide quality coverage in Sámi are extensive, especially with Sámi cultural identity existing across national borders. One solution has been to collaborate with Norwegian and Swedish public broadcasters, NRK and SVT, to produce Ođđasat, a regionally relevant news programme aired every weekday evening. Broadcast predominantly in Northern Sami, the show is subtitled in either Finnish, Norwegian or Swedish to encourage greater knowledge exchange.

In another collaborative move, Yle also partnered with Swedish public broadcaster UR to support Finnish documentary filmmaker Katri Koivula and Saami poet Niillas Holmberg’s project Say it in Saami. The blog and online phrasebook also features five documentaries, with the aim of improving public knowledge of Sámi languages and culture as well as encouraging its greater use in the Finnish language.

Reconciliation and inclusivity

For CBC/Radio-Canada’s Northern Service, CBC North, providing quality coverage across one of the most sparse regions of the second-largest country is no mean feat, but ensuring representative content and inclusivity for over 100 indigenous communities requires organisation-wide projects.

Thankfully the impetus to improve the broadcaster’s reach and representation of Canada’s First Nation population has grown considerably in recent years as the country seeks to reconcile colonial harms, such as the forced removal of indigenous languages and the catastrophic legacy of residential schools.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission has been one such project. Launched in 2015 by the Canadian government, it put forth “94 Calls to Action”, six of which are specific to language and culture, with CBC North playing a crucial role in this process.

Broadcasting in eight indigenous languages – Cree, Inuktitut, North Slavey, South Slavey, Tlicho, Gwich’in, Inuvialuktun, Inuinnaqtun – the PSB spends CAN$24million annually to provide at least 125-hours of weekly indigenous programming, including daily Inuktitut language TV news broadcasts and bilingual election coverage.

More broadly, CBC has also invested heavily in an award-winning indigenous news website, podcasts and three music streaming services dedicated to indigenous music. CBC also has a website dedicated to the 94 Calls to Action, holding the commission to account by measuring and reporting on its progress.

But the reconciliation process doesn’t just involve the provision of more culturally or linguistically relevant content – after all, only 13.4% of those living outside of reserve communities are proficient in at least one indigenous language. It’s also about raising awareness and preserving a rich heritage that many see as being at risk of “extinction”, especially as communities face the implications of an ageing populations and outward migration.

“CBC is currently digitising and archiving 70,000 hours of indigenous language content going back decades, which will be made available to the communities free to use”, CBC North’s Managing Director, Janice Stein, told PMA. “The collection preserves olden time language and rich cultural and traditional knowledge.”

CBC is also improving indigenous representation in the workplace. According to the organisation’s 2018-2021 Diversity and Inclusion Plan, the number of indigenous people employees has grown by 40% since 2014 to 2.1%.

But more needs to be done. “Speakers are aging. They are also not trained in broadcasting or journalism – so there is a lengthy and extensive training component” said Stein. To combat this, Stein highlighted CBC’s one-year paid internships aimed at growing the number of indigenous people working in TV production and as reporters at local stations.

Other inclusivity initiatives include Employee Resource Groups, which offer employees a forum to share workplace experiences (both positive and negative) and Unconscious Bias Training for senior managers to ensure the greater involvement of minority employees in decision making and projects.

"In the North CBC is a key connector of the communities as there are no roads. So communities place high value on the radio and they value the service so they value working to keep it alive".

Engaging all audiences

Italy too has numerous dialects and minority languages, and Sardinian is one of the most widely spoken in the country, with an estimated 1.3million speakers.

The language, native to the Sardinia region was officially recognised by the local government in 1997 and in 1999 by the Italian state as one of the twelve minority languages of the country.

As is the case with many other minority languages around the world, the knowledge of Sardinian is steadily declining, especially among younger demographics. It even features in UNESCO’s Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger.

In December 2016, the Region signed an agreement with Italy’s public broadcaster Rai, which is now broadcasting programmes in the local language on its channels Rai 3 and Radio 1. This also includes dubbing cartoons in Sardinian, in an attempt maintain the language amongst younger populations.

“This announcement has an extraordinary importance in the policies for the Sardinian language that we are carrying out,” said the commissioner of Culture Giuseppe Dessena. “Cartoons become a very attractive vehicle of knowledge, through which children approach the language, a concrete tool adapted to their age, which can be disseminated across the media “.

Native American languages and PBS

Cartoons are also used by the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) in the United States to give space to indigenous culture and languages. In May 2018, PBS Kids announced a new cartoon series – Molly of Denali – which follows the adventures of a Native American girl in Alaska.

Aimed at children aged 4-8, the cartoon contains educational elements coupled with aspects of culture and tradition.

“We believe this series will provide more kids with the opportunity to see themselves represented in our programming and are excited to engage all kids with the culture and traditions of Alaska Native peoples,” said Linda Simensky, PBS’ Children’s Programming vice president.

While the cartoon’s main language is English, the episodes feature several Native languages to expose young children to indigenous languages on TV too.

Alaska’s native languages – more than 20 were officially recognised by the Alaskan State in 2014 – hold a key place of historical and cultural importance and were often a pretext for discrimination, with older generations speaking of receiving punishments when they were young for speaking it.

Yup’ik is one of the main languages, spoken by 65% of people in the Bethel Census Area. Public media works across the State to serve these communities everyday, providing local news and programmes in indigenous languages through 26 radio stations and 4 public tv stations.

Public radio KYUK, for example, has three daily newscasts in Yup’ik and bilingual programming throughout the day. KYUK’s importance is crucial – they are often the only service available for local communities, especially as internet rates can get too expensive for locals who instead turn to the daily broadcasts to get their news.

The station’s survival was threatened by cuts proposed by President’s Trump administration in 2017. Worryingly, the future of these vital services’ remain tenuous under the current administration.

“We believe this series will provide more kids with the opportunity to see themselves represented in our programming and are excited to engage all kids with the culture and traditions of Alaska Native peoples”

From cartoons to interactive content

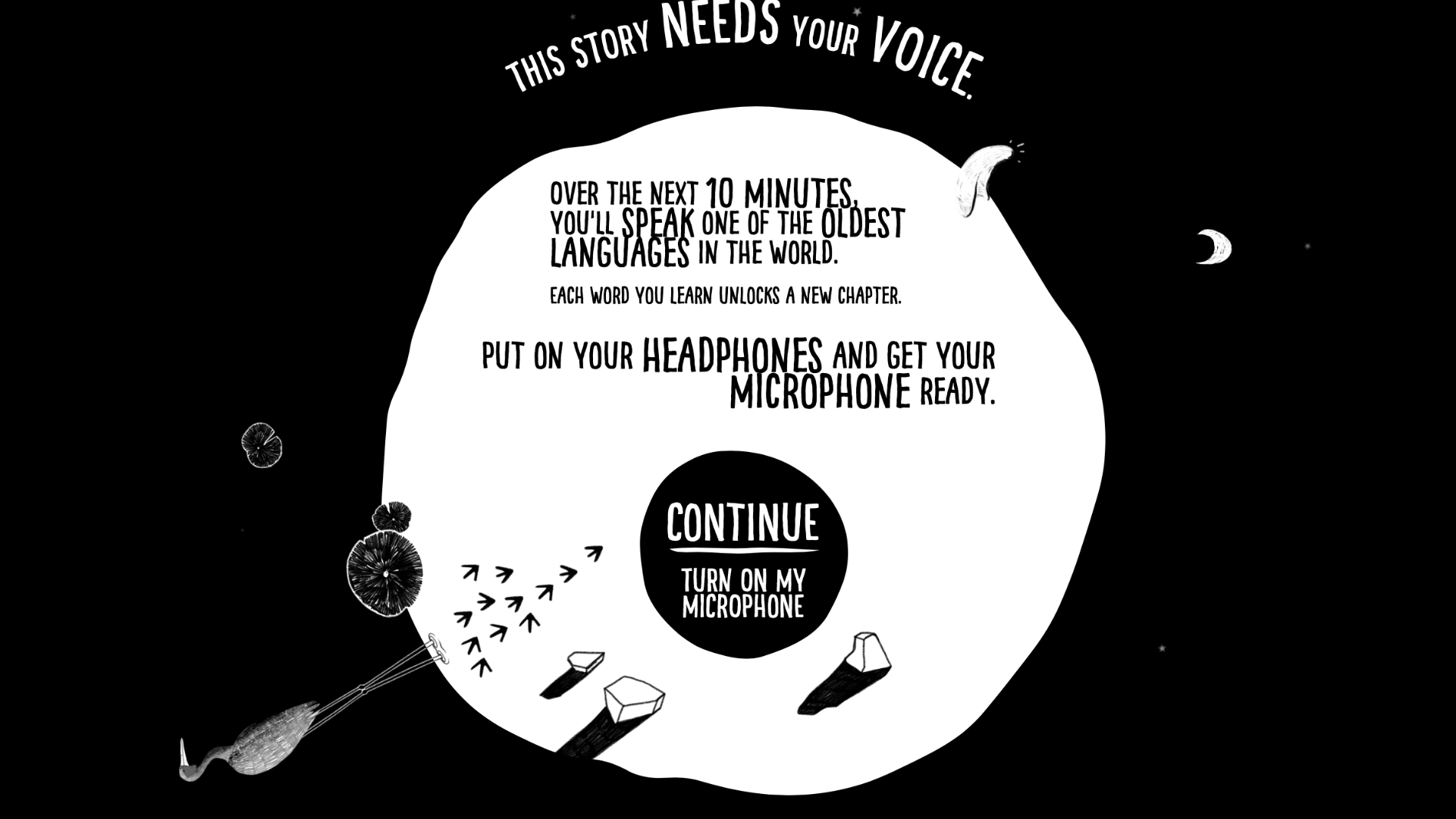

Launched in 2016, My Grandmother’s Lingo is an interactive animation that follows the story of Angelina Joshua, an Aboriginal woman who wants to preserve and protect the future of her Indigenous culture through language.

The online documentary – produced by Australia’s public broadcaster SBS – guides users through Angelina’s story via voice-activated gaming technology and animations, with the aim of raising awareness of Australia’s many indigenous languages, specifically Marra, which is only spoken by three people.

More than 90% of Australia’s Indigenous languages are critically endangered and might cease to exist within the next 30 years.

“My grandmother’s language is important, and it’s up to us keep it alive; to teach it.”

The educational branch of the public broadcaster – SBS Learn – also provides schools with education packs to strengthen students and teachers’ engagement with Indigenous languages.

The Year of Indigenous Languages

As public broadcasters transition to multiplatform public media organisations in the digital age, there is more opportunity than ever to innovate and experiment in alternative ways of representing and being accountable to indigenous communities and their languages.

Yet, this is by no means a conclusive list of examples and there are many more out there. As part of the UN’s Year of Indigenous Languages we want to showcase as many case studies as possible, from large scale inclusivity projects like those at CBC/Radio-Canada, to singular content-driven projects aimed at raising awareness amongst the broader population.

The hope is that these will demonstrate to other media organisations the variety of ways they can make their content and workplaces more accessible, relevant and representative of diverse populations.

Find out more about the UN Year of Indigenous Languages

Header Image: CBC North Iqaluit. Credit: Sebastian Kasten/Creative Commons

Related Posts

3rd December 2018

Best of PSM | NPR engaging younger audiences

Public radio in the US engages students…

23rd November 2018

Best of PSM | VRT’s Taboe – ’Laughing at things you should not be laughing at’

How a mix of human interest stories and…

8th November 2018

Best of PSM | Climate Change – Politics and Actions

Climate change has been a thorny issue…