Independent public media and public interest journalism underpin informed democracy. Yet many outlets are facing greater threats than ever before

Throughout 2020, public service media (PSM) around the world have played a clear and demonstrable role in accurately informing the public and holding power to account, particularly during times of crisis and emergency.

Public media have been indispensable during the pandemic, with many experiencing the highest levels of trust among news outlets as publics seek credible sources of information. In the UK in March, the percentage of the population using the BBC each week rose from 90-94%. In Sweden, the proportion of people who regard SVT as having a “fairly or very high value for society” has risen by 10% to 79%, while in South Korea, KBS has been ranked as the most trusted news brand.

Such trends are not only linked to PSM’s core values of providing a source of accountable, impartial and credible news, but also to their mandates to provide universally accessible content of public interest. For CBC/Radio-Canada, its regional and multilingual services have proved pivotal during COVID-19, giving it a monthly audience spanning two-thirds of the Canadian population. Meanwhile, Australia’s ABC brought their audience into the newsroom (figuratively), using over 100,000 of their questions to shape their news coverage of COVID-19.

Public media have been indispensable during the pandemic, with many experiencing the highest levels of trust among news outlets as publics seek credible sources of information.

As in the countries above, French, German, Japanese, South African and American public media have also seen a growth in trust and audiences as they stepped in to provide educational resources amid school closures.

And with many elections around the corner, the role of public media and public interest journalism in delivering accurate and verifiable information has never been so important nor more challenging as they continue to operate under unprecedented circumstances.

Yet COVID-19 isn’t the only challenge facing public broadcasters and other public interest media. Nor does it make its impact in isolation; rather it compounds many of the threats already faced by journalists and media workers.

Despite the vital role of public service and public interest media in reporting coronavirus, the pandemic has offered some governments a guise through which to roll out laws and restrictions on critical media as well as propagate populist discourse against those holding power to account.

Journalist safety is in decline and impunity for their attackers is on the rise. From Belarus to Hong Kong and the United States, covering protests has become more than a double-edged sword, whereby the pandemic only adds to the risks posed by projectiles, arbitrary arrests and harassment from authorities. In Germany, journalists for ARD, ZDF and other trusted outlets have, on numerous occasions, faced intimidation and physical harm from protesters at so-called “anti-vax” rallies among others.

Journalist safety is in decline and impunity for their attackers is on the rise.

Another trend is the growing rejection and revocation of visas for foreign journalists, who help to fill information voids where local outlets have been forced to close due to new laws or poor funding.

This all takes its toll on democracy. The implication of these restrictions, vague legislation and threats against journalists can inspire self-censorship and at its worst, stop the flow of critical and verifiable news that is essential for citizens to make informed decisions both during elections and in keeping safe.

The Public Media Alliance has been closely following the situation faced by some of our members as well as other PSM and public interest outlets since the start of the pandemic. Here we highlight some of our ongoing concerns in Hong Kong, Pakistan, Slovenia, Tanzania and the United States.

Country by Country

Click on the countries below to find out more about the challenges posed by COVID-19 on media around the world.

Hong Kong

In late June, the Chinese government imposed a new wide-ranging security law for Hong Kong. The law was said to target secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with foreign forces. However, as we’ve noted in our May Call Out, the law is a pretence to smother press freedom and silence critical voices. The law’s stifling of freedom of the press is particularly alarming since this freedom is meant to be guaranteed under the “one country, two systems” constitutional principle.

Read more: Another dark week for press freedom and critical voices in Hong Kong

The law is a further concern for the negative impact it will have on the democracy of Hong Kong. Since the law’s deployment, we have seen the arrests of hundreds of pro-democracy protesters and activists. Press freedom is being crushed, both directly — in the form of raids and arrests — and indirectly, through self-censorship.

There has also been greater pressures on the public broadcaster, Radio and Television Hong Kong (RTHK), a news organisation that has long held a history of strong editorial independence. The recent removal of news content and satirical programmes highlight the influence exerted by the stricter media environment, while recent board appointments are said to have strong ties to Beijing.

The new national security law comes in what Freedom House has deemed a new era of Chinese disinformation, where there has been exerted influence by the Chinese Government over the media and information space both locally and internationally. Particularly with the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been attempts to manipulate coverage and limit free speech.

The erosion of press freedom in Hong Kong was noted in the 2020 World Press Freedom Index where the special administrative region fell seven spots between 2019 and 2020, from 73 to 80. There is expected to be a substantial decline in next year’s report.

Pakistan

Independent journalism in Pakistan has endured significant blows throughout 2020. While there were media freedom gains in recent years, these have receded significantly and Pakistan fell three spots in this year’s RSF World Press Freedom Index to 145 out of 180 nations.

Since 1992, at least 61 Pakistani journalists have been killed in connection with their work, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Public interest journalism plays an important role in Pakistan’s media landscape but operates in a political environment that typically punishes it rather than reward it. This year alone, Pakistani journalists have faced broadcast restrictions and suspensions at the whim of the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (PEMRA); death threats and online abuse; and arrests, assault, and even abduction at the hands of authorities. Most notably, Pakistani journalist Mir Shakil-ur Rahman, the Editor-in-Chief of the Jang Media Group, was arrested on 11 March and has remained in prison for more than 190 days without bail. A number of academics, human rights activists, journalists, Pakistani expatriates, media and human rights bodies have so far called for Rahman’s release and fair treatment. Today he is seen as a symbol of press freedom.

Most recently, PTV journalist, Shaheena Shaheen, was shot dead in Balochistan, the second female journalist to be killed in Pakistan this year.

There appears to be no moderation of media freedom violations in sight; most recently, PEMRA ordered private channels to ensure drama scripts were in line with “Pakistani values”, a clear attempt by the government to limit editorial independence within media organisations.

Read more: Space for independent and critical media continues to shrink in Pakistan

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought with it additional challenges to public interest media in Pakistan. The Pakistani government has used the pandemic as a cloak to stifle critical voices through media directives which could restrict much needed accuracy and responsible reporting on COVID-19. As of May, the virus had killed three Pakistani media workers and infected 156 others, according to the Dawn newspaper.

Read more: UNPO: Pakistan: “Worst of the Times” for Country’s Press Freedom

International Media Support has also noted that public interest journalism is one of Pakistan’s biggest coronavirus victims due to the challenges of navigating clear attempts by the state to restrict open discourse and critical voices along with the financial difficulties that existed pre-COVID-19, which have worsened due to the pandemic.

Slovenia

As in Hungary and Poland, press freedom in Slovenia has been deteriorating at an alarming rate. In mid-March, as Janez Janša secured his position as Slovenia’s prime minister for the third time, his administration left no time in stating its disdain for critical reporting. This coincided with a rise in online smear campaigns and death threats towards journalists working for public broadcaster Radiotelevizija Slovenija (RTVSLO) as well as foreign reporters, creating a hostile environment for journalists to safely report on pressing issues, such as COVID-19.

In July, Janša’s government set about creating proposed legislative changes to three media laws, including an amendment to a law regarding the functioning of RTVSLO under the guise of creating more “media pluralism” in Slovenia. Despite ongoing budget restraints and its role as a key source of information and educational content during the pandemic, part of the proposed amendments aim to defund RTVSLO by around 20% annually, including a cut to income from licence fee payments. Under proposals, this funding would then be redistributed to Slovenia’s Press Agency, STA, and privately owned media, some of which are run by Janša supporters. According to IPI, some pro-government media are also funded by outlets linked to Hungarian Prime Minister Victor Orban, who has “dismantled media freedom and pluralism in Hungary over the past 10 years by pioneering a system of media capture inside the EU”. Such changes would undermine the legitimacy and capacity of the public broadcaster to serve its audiences during the global pandemic and beyond, and have grave consequences for Slovenia’s media landscape and democracy.

READ MORE: Slovenia’s public broadcaster pressured by government

Slovenians had until 5 September to participate in a public consultation to share their views about the proposed changes to the media laws. STA reported that “Opinions clashed about the quality and impartiality of [the] public broadcaster.” Meanwhile, according to Total Slovenia News, the debate continues as the public broadcaster and opposition party calls on the government to withdraw the proposals to amend the media laws. It wrote that TV Slovenija director, Natalija Gorščak, believes “the legislative changes were not only an attack on the public broadcaster, but on the Slovenian cultural identity and language in general.”

Tanzania

When it comes to press freedom, Tanzania has made history for all the wrong reasons: Reporters Without Borders (RSF), in its 2020 World Press Freedom Index, notes that none of the 180 countries it ranks have plummeted as much in recent years as Tanzania, which has fallen 54 places to 124th out of 180 countries in just seven years.

The decline is largely attributed to the rule of President John Magufuli, who ascended to power in 2015. Since then, Tanzanian journalists have been the targets of concerted attacks and have seen unprecedented levels of clampdowns, self-censorship, and a shrinking of civic space, as we reported in December 2019 on the media freedom crisis facing the country. For journalists such as Erick Kabendera — who spent seven months in prison on seemingly trumped up charges due to criticisms levelled against the government — there is the very real threat of imprisonment to silence their critical voices. Despite calls over the years from international organisations there has been little to no change.

Throughout 2020, there have been additional blows to the already nosediving press freedom in the East African nation. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the challenges faced by media workers through financial difficulties due to salary cuts, layoffs, and dwindling revenue. The Tanzanian government has also considerably added to the burden by making it more difficult for those who can work to function in the media landscape. Journalists and media outlets have been sanctioned, suspended, and even temporarily banned for their COVID-19 reporting.

Read more: Tanzania: Regulator poses tighter restrictions on media

In July, the government passed further new restrictions in the form of its Electronic and Postal Communications (Online Content) Regulations, which have added to digital rights repression in the country. In September, the Media Council of Tanzania (MCT) took aim at media houses for what it said were deteriorating media ethics and professionalism. Furthermore, the Tanzania Communications Regulatory Authority (TCRA) imposed even more repressive media laws by mandating local radio and television stations to seek permission from the government to broadcast foreign content.

Read more: Tanzania: Freedoms Threatened Ahead of Elections

These developments come at a troubling time. Tanzania will hold a general election on 28 October — its first since President Magafuli was elected — and now more than ever there is the need for pluralism in the media landscape and greater press freedom as a whole. Deutsche Welle Chief, Peter Limbourg, has deemed the new law on foreign media a “clumsy attempt to suppress critical voices before the elections in Tanzania” but has also noted that such a “far-reaching form of state censorship” is difficult to combat.

United States of America

While freedom of the press is guaranteed by the United States’ Constitution, there have been steady declines in press freedom in the US. These declines are against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic and the upcoming 2020 US election on November 3.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought with it economic uncertainty and journalist safety concerns, both of which can impact democracy. More than 36,000 media workers have lost their jobs, been furloughed, or had pay cuts since the beginning of the pandemic. The viability of local journalism — long in decline — has worsened due to COVID-19.

US public media are facing both similar and unique challenges. In June, national public broadcaster, the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), cut around 6% of its workforce due to the pandemic and made departmental changes. National Public Radio (NPR) reported a decline in listening figures due to fewer commuters while its CEO anticipated a deficit of $30 million to $43 million when the new fiscal year commences in October. Even though US public broadcasters received some emergency funding due to the pandemic, public media advocacy group, Protect My Public Media, called for further emergency funding for local public media stations.

Read more: Congress proposes additional federal funding for US public media

Meanwhile, international journalists working for the Voice of America (VOA) have been left in a precarious situation due to a visa review process by the US Agency for Global Media (USAGM). Most recently, on 16 September, Congress members sought answers on visa denials which they believed could endanger the lives of journalists and the mission of USAGM’s networks.

VOA has faced wider challenges this year following the confirmation of Michael Pack – a Trump loyalist – as head of the USAGM. His appointment has led to serious concerns for the organisation’s editorial independence amidst a purge of senior staff linked to the international outlets that USAGM oversees. His appointment also led to the resignation of VOA’s Director, Amanda Bennett.

Read more: Fears for Voice of America’s editorial independence

The Black Lives Matter protests which began in late May further challenged media outlets, both public and private. Journalists faced a record number of threats, arrests by law enforcement, and even physical attacks for doing their jobs. Journalists covering the protests were attacked more than 100 times in the week after the protests began. International journalists were also attacked, as seen with public media organisation CBC/Radio-Canada, whose Senior Correspondent Susan Ormiston and her team were shot at with rubber bullets. Two Australian journalists were also assaulted by police officers as they executed their jobs.

Since 26 May 2020, there have been over 813 press freedom incidents across the US according to the US Press Freedom Tracker.

The COVID-19 pandemic, funding challenges for public media, and targeted attacks on journalists threaten democracy, freedom of the press, and the essential role journalists play in protecting constitutional rights. With the 2020 US election just under two months away — all amid a global pandemic — the role of a free and independent US media is more important than ever. As part of public media’s democratic role, it must provide verified, timely, and unbiased information during election periods to empower citizens to make informed decisions. But the current challenges raise serious concerns as to how effectively US media organisations can execute their essential role.

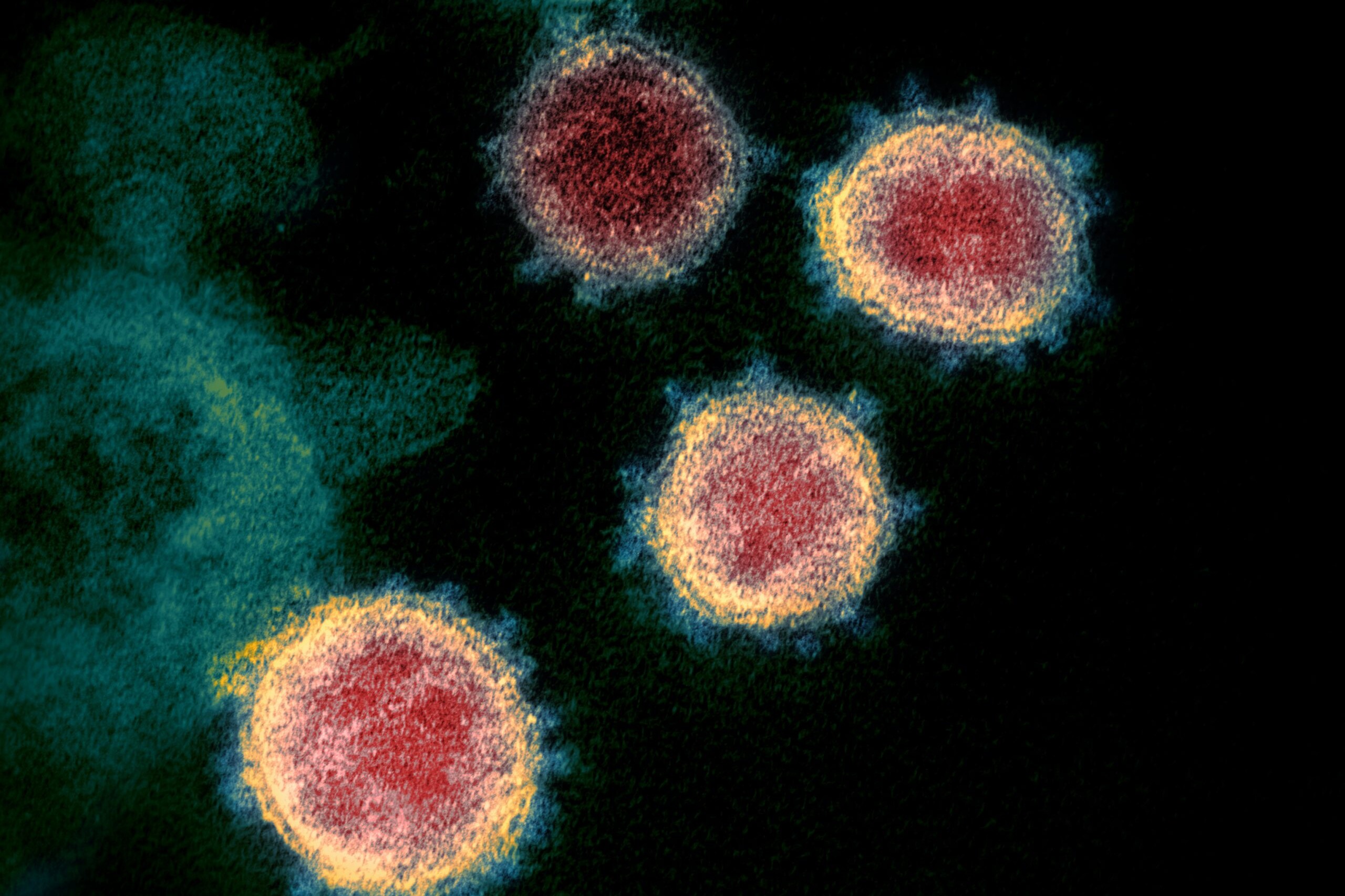

Header Image: This transmission electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2—also known as 2019-nCoV, the virus that causes COVID-19—isolated from a patient in the U.S. Credit: NIAID-RML/Creative Commons

Related Posts

7th July 2020

COVID-19: Amplifying the threats to public media

From political interference to funding…

15th May 2020

Global Call Out: COVID-19 takes its toll on independent media

It is essential that citizens have…