Media pluralism is necessary for democracy to function effectively. But clampdowns and suspensions, repressive laws and the expulsion of foreign media have placed pluralism under threat globally. In this piece, we explore the limitations on pluralism witnessed in Belarus, Hong Kong, Tanzania and Poland.

By Desilon Daniels

A pluralistic media landscape allows for divergent political and ideological views and better enables the representation of different cultural and social groups. Pluralism also ensures competition within the media marketplace and for citizens this not only means greater access to a variety of education, information, or entertainment content but also greater opportunities to make their views known.

Public service media (PSM), in particular, have an important role to play in pluralism by serving as a public source of diverse opinions and impartial information, especially during election periods. The Council of Europe notes that public service media “are particularly suited to foster pluralism and awareness of diverse opinions, notably by providing different groups in society with an opportunity to receive and impart information, to express themselves and to exchange ideas.”

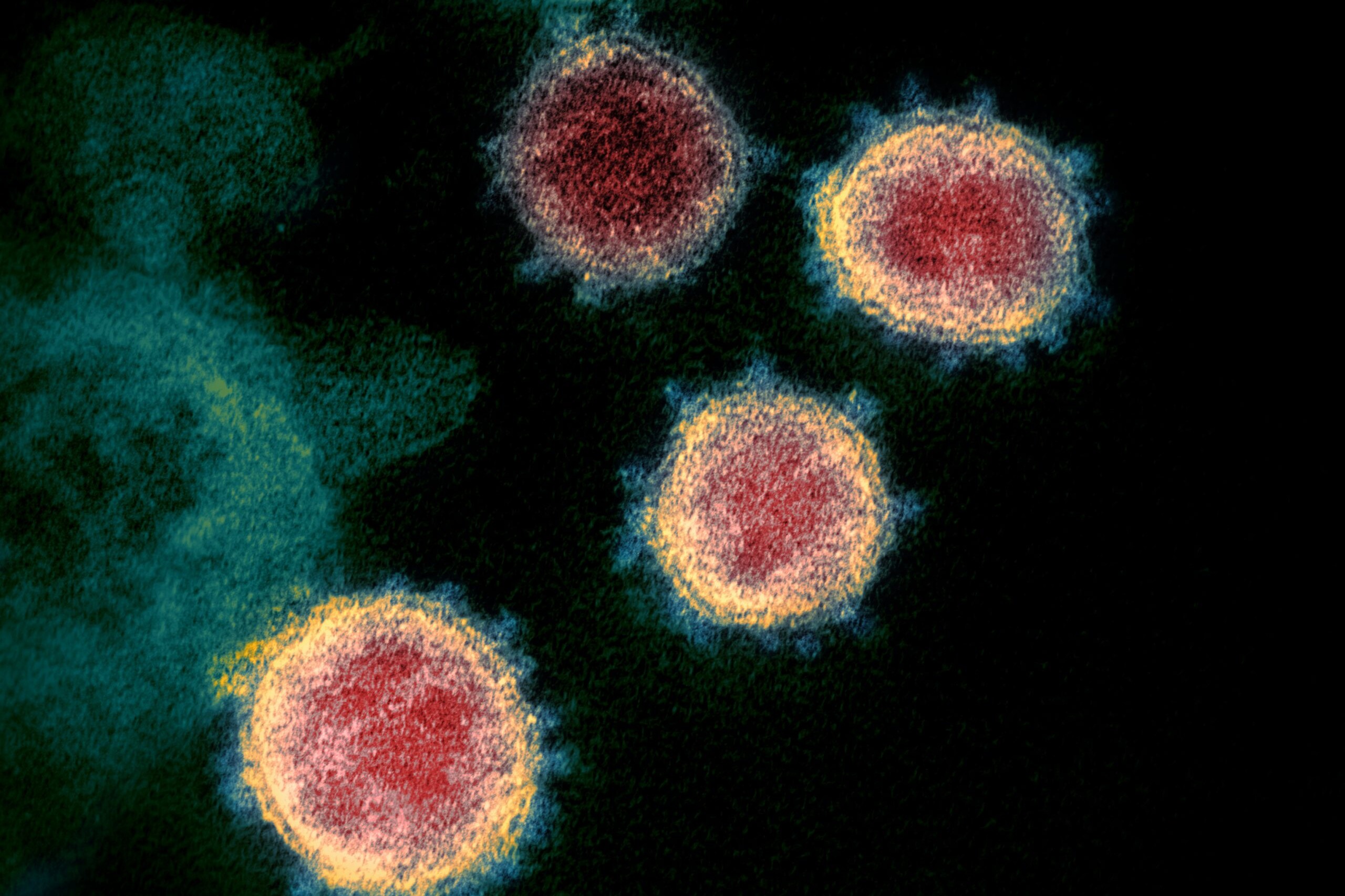

But around the world, media pluralism is under threat. Public media and public interest media require a pluralistic environment to function effectively. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought with it increasing attacks on media pluralism. Furthermore, as many countries hold elections this year, there are growing concerns regarding the stifling of pluralism and, with it, the suppression of divergent opinions, ideas and access to unbiased information for voters.

Limiting diverse media

Pluralism is not solely limited to diverse voices but also includes diverse media types. Repressive governments have recognised the power of social media and have taken measures to censor or outright persecute citizens for the content they post online.

In Belarus – where the state owns all television stations and a majority of newspapers – citizens need access to other media types in order to encounter divergent opinions and ideologies and to share their own. But, with the government clamping down on independent media, people have fewer diverse sources available to them. Most recently, in response to the record-breaking nationwide protests following the re-election of President Alexander Lukashenko, the government has honed in on interfering with internet access and restricting online content, thereby limiting both pluralism and free speech. The move is seen as an attempt to demobilise and silence protesters. In response, protestors have turned to privacy apps to organise themselves. The Belarusian government has long attempted to exert control over online content, as seen with its controversial news media law in 2018, which allowed the blocking of social media networks and other sites.

Similar attempts by governments to control online content has been seen around the world. Governments have passed or considered social media regulations in what they say is the public good but ultimately use these laws to censor their populations and limit access to a plurality of views and opinions. A recent example can be found in Tanzania where, in July, the government passed the Electronic and Postal Communications (Online Content) Regulations Act, which represses online speech, access to information and privacy by further regulating the licensing and taxation of radio, television and online broadcasters as well as bloggers and online discussion forums.

Clampdown on foreign media

But governments are not just limiting pluralism by interfering with internet access or applying repressive laws to online content. Governments have doubled down on restricting pluralism by instituting media clampdowns and outright expulsions. Local journalists have borne the brunt of these attacks, but foreign media have not been exempt: more and more, they are being targeted by political leaders.

The expulsion of foreign media is particularly concerning since, in many countries, they provide independent and critical coverage that might have not been available otherwise. Their critical voices provide not just local citizens but the wider world with the reality of national events. Their voices ultimately lend to democracy.

In Belarus, foreign media outlets recently had the accreditation of their Belarusian correspondents removed by authorities while two Associated Press reporters were deported, CNN reported in late August. Most recently, Belarusian authorities went even further and cancelled the existing accreditation of all journalists working for foreign media in the country.

But the targeting of foreign media is happening against the backdrop of an oppressive media landscape, which local journalists have long faced. The media landscape is mostly state run or state affiliated, with minimal independent media. Independent media face constant harassment, crackdowns, and other attempts to curb freedom of speech. The leadup to the 2020 general election on 9 August brought even worse conditions. More than 40 journalists were arrested in the three months before the election for their coverage of demonstrations and, since then, at least 141 others have been detained. Tensions were heightened following the re-election of President Lukashenko and his subsequent unannounced inauguration, resulting in the largest nationwide protests in the country’s history.

Video: Exclusive report from RSF’s correspondent in Belarus. Source: Reporters without Borders

Political leaders in Poland have also become increasingly hostile to foreign media. In July, the Leader of the governing Law and Justice party (PiS) revealed the government’s plan to pass a new law before 2023 to limit the number of foreign-owned media in the country. The law is part of PiS’ plans to “repolanise” the media landscape due to the criticisms levelled against the government by private media, which are typically owned by foreign companies. The proposed tightening up of foreign media is part of a wider clampdown on the criticality of independent media in Poland. Pluralism has been in decline in recent years and the Polish public broadcaster, Telewizja Polska (TVP), is now widely regarded as an extension of the state, following suit with neighbouring Hungary.

But shrinking pluralism through attacks on foreign media is certainly not limited to Europe. Most recently in Tanzania, the Tanzania Communications Regulatory Authority (TCRA) imposed even more repressive media laws by mandating local radio and television stations to seek permission from the government to broadcast foreign content.

Read more: Tanzania: Regulator poses tighter restrictions on media

This is all part of a wider fall in press freedom for the East African country, which fell from 70/180 in RSF’s 2013 World Press Freedom Index to 124/180 today. The decline is linked to concerted attacks on the press and a record number of clampdowns, suspensions, bans, and levels of self-censorship, as we reported in our latest Call Out. Ultimately, these have negatively impacted on pluralism in the Tanzanian media sector.

In Hong Kong, foreign journalists have been caught in the middle of tensions between China and the United States and are facing long visa delays. Western journalists in mainland China were already facing restrictions and even the removal of credentials, as seen with journalists from three major US newspapers in March. Australia’s last two journalists were forced to flee China in early September due to tensions between the two nations. Furthermore, The Washington Post reported that, for the first time in 40 years, it will no longer have a single correspondent in China.

Read more: Further restrictions on media freedom in Hong Kong

The latest developments in Hong Kong bring the semi-autonomous state closer to the shrinking pluralism long seen on the mainland. Most recently, the Hong Kong Police Force announced new accreditation rules, which would only accept journalists from “internationally recognised and renowned” foreign media and media organisations that are registered with the government’s information system. These new rules not only limit the diversity of media in Hong Kong, but also the territory’s increasingly limited free press.

The ability to access a broad range of information is critical for the effective running of any consolidated democracy, especially in times of election. Yet the growing repression of journalists and access to diverse media – including public media – not only serves to stifle debate but also the availability of factchecked and verified news that is so essential to combatting the ongoing global pandemic.

Related Posts

1st October 2020

Further restrictions on media freedom in Hong Kong

New developments have painted an even…

24th September 2020

Shutdowns, layoffs and court cases: The clampdown on independent media in the Philippines continues

The ongoing repression of independent…

23rd September 2020

Call Out: COVID-19 compounds risks to public media and their critical role in democracy

Independent public media and public…

19th August 2020

Tanzania: Regulator poses tighter restrictions on media

There are serious concerns that new…